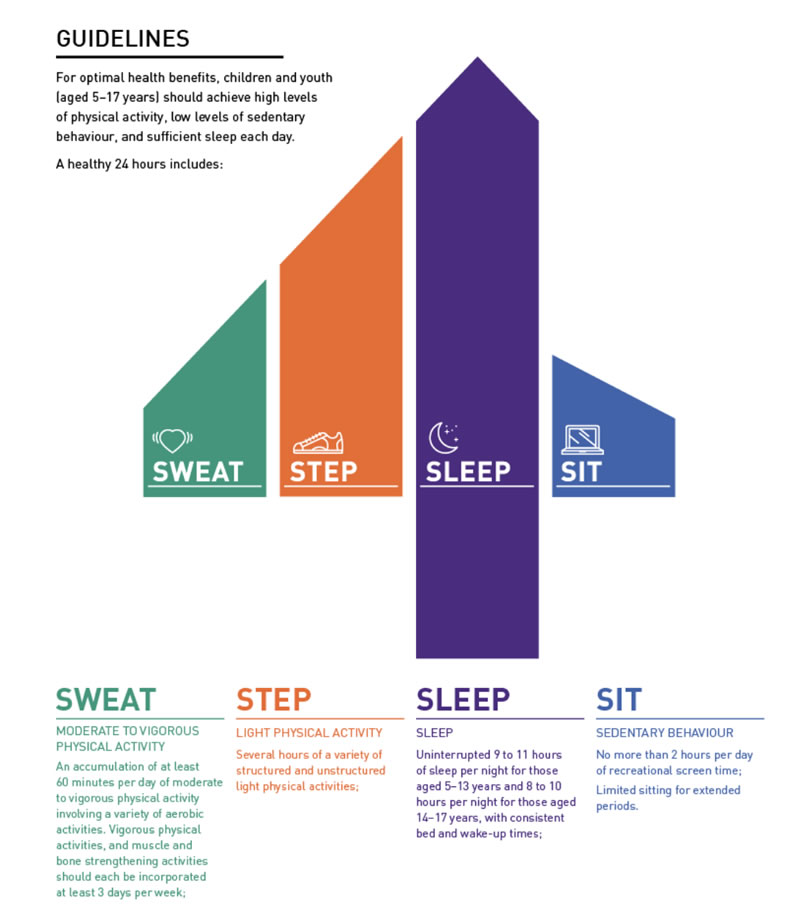

Dr. Jeremy Walsh, a Professor at the University of British Columbia, along with his colleagues, recently published a health study of over 4,500 U.S. children, ages 8 to 11 years conducted between September, 2016 and September, 2017. Their findings help us appreciate the complexity of the challenges facing children today as well as facing parents attempting to balance the lives of their children with current technology. These researchers found that superior thinking or cognition was associated with limited screen time, adequate sleep and exercise in this population of children. These children were part of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Project, a 10 year, long term observational study across 21 sites in the United States. The children were evaluated with the Canadian 24 hour movement guidelines for children and youth. These guidelines, as diagramed below, recommend 9 to 11 hours of sleep, 2 hours or less of recreational screen time and at least 60 minutes of physical activity every day for youth 5 to 13 years of age.

These guidelines are consistent with those recommended by the World Health Organization and the National Sleep Foundation. (Neither organization nor the American Academy of Pediatrics has a recommendation about screen time for children less than five years of age.) To measure thinking, researchers use a series of tests evaluating language, memory, executive function, attention and processing speed. On average, children in this study spent 3.6 hours engaged in recreational screen time each day. They met an average of only 1.1 recommendations. Fifty-one percent met the sleep recommendation, 37% screen time and 18% physical activity. Almost 30% did not meet any recommendations and only 5% met all 3! What is important about these recommendations is not that they are based alone on good sense or unwarranted worry. These recommendations are based on findings such as that generated by Dr. Walsh and his colleagues. Good thinking was associated positively with each additional recommendation met. Compared with meeting no recommendations, meeting all 3 recommendations was associated with superior thinking. The link between thinking and screen time potentially reflects an interruption of the stress recovery cycle that children need for growth observed by other researchers. The cycle is simple. As Dr. Eduardo Bustamante of the University of Illinois in Chicago describes, each minute spent on screens necessarily displaces a minute from sleep or cognitively challenging activities. Science is complicated, evaluating multiple variables simultaneously often leads to correlation but not necessarily a cause and effect understanding. We do not know whether these associations are due to the absence of more cognitively stimulating activities such as reading or other novel situations such as visiting a museum or library, or whether it is due to reducing screen activities specifically. Some findings show that people who are avid gamers have better visual spatial abilities and faster processing speeds and reactions times but others show impairment in different types of attention and working memory. The advantage gained in one area may be costly in another area of development.

A new Pugh Research Center Survey finds that 52% of United States teens report taking steps to cut back on their mobile phone use and have tried to limit their use of social media or video games. Fifty-four percent of U.S. teens say they spend too much time on their cell phones and two thirds of parents expressed concern over their teen’s screen time. Overall, 56% of teens associate the absence of their cell phone with at least 1 of 3 emotions: loneliness, feeling anxious or upset. Females are more likely than boys to feel anxious or lonely without their cell phones.

Parents too are anxious about the effects of screen time on their children. A separate Pugh survey found that at least a third of parents report themselves spending too much time on their cell phones. Additionally, 51% of teens reported they often or sometimes find their parents and caregivers to be distracted by their own cell phones when they are trying to have a conversation with them. Further, when it comes to evaluating their own online habits, teens expressed mixed views about whether or not they themselves spend too much time on various screens. Roughly half believe they spend too much time on their cell phone while 41% report they spend too much time on social media. Interestingly, only about one quarter report they spend too much time playing video games. Most teens report they check their cell phones for messages as soon as they wake every day. Finally, it is of interest that parents who expressed heightened worries about their teens screen exposure are more likely to say they set screen time restrictions than those who did not. Some 63% of parents worry a lot or some about their teen’s screen time. They say they at least sometimes set limits on that behavior but that share falls 47% among parents who worry “not too much” or “not at all.” Though parents generally report that they are least somewhat confident that they know how much screen time is appropriate for their children, it appears from this series of studies that way too much screen time is being spent in light of the lessons learned from good scientific data.

From now on when I’m asked about this topic I will refer parents and other professionals to the Canadian Guidelines. They are balanced. They make sense. They provide a very clear mandate about what is best for our children.